Two are always more interesting than pne.

No?

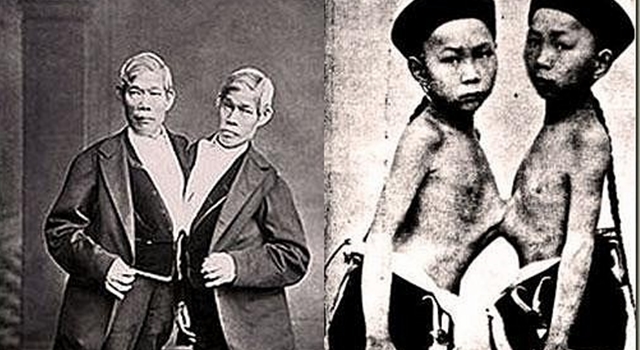

In classic literature it is often the foil or “other” who reveals something crucial about the hero. So it goes in the case of Chang and Eng Bunker, the original Siamese twins, whose career of posing as an “other” on stages across the country would come to reveal much about the American psyche. In Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and Their Rendezvous with American History (Liveright, $28.95), Yunte Huang recounts the peculiar, and often ironic, rise of Chang and Eng from sideshow curiosity to Southern gentry—an unlikely story that exposes the foibles of a young republic eager to tyrannize and delight in the abnormal.

First “discovered” by the enterprising Scotsman Robert Hunter in Siam, the twins left their family behind on April 1, 1829 to set sail for Boston. The whirlwind tour—through Boston, London, New York, Philadelphia and New York—was only supposed to last five years. But the land they wandered into was one newly taken with such curiosities “imported” from exotic lands, a nation reveling in the pages of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame; a home, in other words, obsessed with “monsters.”

Famous for their quick wit (they once refunded a one-eyed man half his ticket because he “couldn’t see as much as the others”), Chang and Eng became a nationwide sensation, heralded as living symbols of the humbugged freak. Their unrivaled success quickened the birth of mass entertainment in America, leading to the minstrel show and the rise of showmen like P.T. Barnum. Breaking off from their manager in 1832 to strike out on their own, they eventually earned enough to leave show business altogether and settle in Wilkesboro, North Carolina.

And it is here that we encounter a twist. Miraculously, despite the 1790 Naturalization Act which limited citizenship to “free white persons” (until 1952), Chang and Eng became American citizens under the Superior Court of North Carolina. They then went on to marry two white sisters—Sarah and Adelaide Yates—and father 23 children despite the interracial marriage ban (in place until 1967). They owned 18 slaves and became staunch advocates for the Confederacy, so much so that their sons fought for the South during the Civil War.

Bringing an Asian-American perspective to the lives of the Bunker twins for the very first time, Huang reveals that it was perhaps their very “otherness” that worked for them: they were neither one individual, or quite two. As Chinese immigrants before the rise of anti-Asian sentiment in the states, they were neither white or non-white; in US Census Bureau documents, they were deemed “honorary whites.” Thus they joined the ranks of the Southern gentry.

Animating a history we have never seen clearly before, the book is not only a sensational biography, but a profound investigation into our enduring penchant for finding feast in the abnormal—a tradition, Huang reveals, as American as apple pie. One that, in perhaps the greatest “act” of their career, Chang and Eng were able to manipulate and subvert.