On Thanksgiving Day 1950, American-led United Nations troops were on the march in North Korea. U.S. Marine and Air Force pilots distributed holiday meals, even to those on the front lines. Hopes were high that everyone would be home by Christmas. But soon after that peaceful celebration, American military leaders, including General Douglas MacArthur, were caught off guard by the entrance of the People’s Republic of China, led by Mao Zedong, into the five-month-old Korean War.

Twelve thousand men of the First Marine Division, along with a few thousand Army soldiers, suddenly found themselves surrounded, outnumbered and at risk of annihilation at the Chosin Reservoir, high in the mountains of North Korea. The two-week battle that followed, fought in brutally cold temperatures, is one of the most celebrated in Marine Corps annals and helped set the course of American foreign policy in the Cold War and beyond. Incorporating interviews with more than 20 veterans of the campaign, American Experience: Battle of Chosin recounts this epic conflict through the heroic stories of the men who fought it.

The PBS Distribution documentary will be available on DVD on January 24; the program will also be available for digital download.

The events that led to the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir started five months earlier when Korea unexpectedly became the battleground for the first hot conflict of the Cold War. Split across the middle at the 38th parallel in the political settlement that followed World War II, the Korean peninsula had solidified into separate states by 1950.

The two new governments symbolized the rising struggle between the world’s dominant political ideologies: democracy and communism. The Soviet Union and Mao Zedong’s new Communist China supported North Korea while South Korea had the backing of the United States and other Western democracies. This balance of power held until June 25, 1950, when North Korea led a surprise attack against South Korea and quickly overran most of the Korean peninsula.

The United Nations Security Council approved a resolution to end the hostilities in Korea and authorized the United States military to lead a multi-national force against North Korea. President Harry Truman told the world that the United States would take “whatever steps were necessary” to contain Communist expansion in Korea. This included the possibility of unleashing nuclear weapons on China. Fears of World War III filled the news.

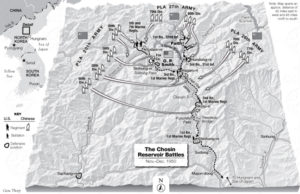

Under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, American-led forces had turned back North Korea’s aggression. MacArthur then set his sights on quickly pushing north to the Chinese border and reuniting the country under democratic rule. On the eve of MacArthur’s final offensive, the First Marine Division was strung out on a single 78-mile-long supply route leading to the Chosin Reservoir.

Mao Zedong had won a long and deadly civil war a year earlier and united China under the communist flag. When MacArthur’s UN forces threatened his border in the fall of 1950, Mao decided to act. By late November 1950, tens of thousands of Chinese soldiers had quietly infiltrated North Korea and surrounded MacArthur’s forces. On the night of November 27, Mao sprung his trap at the Chosin Reservoir.

The worst of the Chinese onslaught landed on the forces encamped in the hills around the Chosin Reservoir—the First Marine Division, under the command of General Oliver P. Smith, and a small, attached Army unit. Night after night, Mao’s army swept down from the hills and attacked the vastly outnumbered American troops.

The only hope for the surrounded men was to fight their way back to the coast, a perilous journey into the teeth of a subarctic winter, through tens of thousands of Chinese soldiers waiting in the high ground above the single road out. For the next two weeks, General Smith’s men fought brutal battles against the Chinese in some of the harshest conditions American forces had ever experienced. Dead bodies, frozen in grotesque and contorted shapes, littered the battlefield. Finally, 14,000 surviving troops made their way back to safety.

The carefully staged withdrawal succeeded and also inflicted devastating losses on the enemy. Two Chinese divisions were entirely destroyed, and an estimated 40,000 Chinese soldiers were killed.

Thousands of North Korean refugees were also fleeing south, many trailing the column of Marines. Nearly 100,000 refugees were part of the massive evacuation of American and UN troops out of North Korea.