It’s a shame many still don’t know his name. Or his genius.

Nikola Tesla invented the radio, the induction motor, the neon lamp, and the remote control. His scientific discoveries made possible X-ray technology, wireless communications, and radar, and he predicted the Internet and even the smart watch. Today, he is hailed as a visionary by the likes of Elon Musk (whose electronic cars bear his name) and Larry Page, the founder of Google. His image appears on stamps, the Encyclopedia Brittanica ranks him as one of the ten most interesting historical figures, and Life magazine lists him as one of the one hundred most famous people of the last millennium. And yet, his contemporaries and fellow inventors Thomas Edison and Guglielmo Marconi achieved far greater commercial success and popular recognition.

In Tesla: Inventor of the Modern (W. W. Norton & Company, $26.95), Richard Munson asks whether Tesla’s eccentricities eclipsed his genius. Ultimately, he delivers an enthralling biography that illuminates every facet of Tesla’s life while justifying his stature as the most original inventor of the late nineteenth century.

Harvey Sachs’s Toscanini: Musician of Conscience (Liveright, $24.95) recounts the 68-year career of conductor Arturo Toscanini, an artist celebrated for his fierce dedication, photographic memory, explosive temper, impassioned performances and uncompromising work ethic. Toscanini collaborated with Verdi, Puccini, Debussy, and Richard Strauss; undertook major reforms at La Scala and the Metropolitan Opera; and eventually pioneered the radio and television broadcasts of the NBC Symphony.

His monumental achievements inspired generations, while his opposition to Nazism and fascism made him a model for artists of conscience. In this persuasive and compelling new biography, Sachs illuminates the crucial―the central―role Toscanini played in our musical culture. Set against the roiling currents of twentieth-century Europe and the Americas, Toscanini is a “necessary” portrait of this “complex, flawed, but noble human being and towering artist” (Wall Street Journal) whose peerless influence reverberates today.

His monumental achievements inspired generations, while his opposition to Nazism and fascism made him a model for artists of conscience. In this persuasive and compelling new biography, Sachs illuminates the crucial―the central―role Toscanini played in our musical culture. Set against the roiling currents of twentieth-century Europe and the Americas, Toscanini is a “necessary” portrait of this “complex, flawed, but noble human being and towering artist” (Wall Street Journal) whose peerless influence reverberates today.

A book about Jimmy Carter, 39th President of the United States, as a beach read? Absolutely. And much more entertaining than, say, a collection of Peanuts. In President Carter: The White House Years (Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press, $40) Stuart E. Eizenstat presents a comprehensive history of the Carter Administration, demonstrating that Carter was the most consequential modern-era one-term U.S. President.  The book is behind-the-scenes account of a president who always strove to do what he saw as the right thing, while often disregarding the political repercussions.

The book is behind-the-scenes account of a president who always strove to do what he saw as the right thing, while often disregarding the political repercussions.

Adventures of a Young Naturalist–The Zoo Quest Expeditions (Quercus, $26.99) is the story of voyages taken by David Attenborough. Staying with local tribes while trekking in search of giant anteaters in Guyana, Komodo dragons in Indonesia, and armadillos in Paraguay, he and the rest of the team contended with cannibal fish, aggressive tree porcupines, and escape-artist wild pigs, as well as treacherous terrain and unpredictable weather, to record the incredible beauty and biodiversity of these regions. Don’t take our word for it: Says Barack Obama of Attenborough: “A great educator as well as a great naturalist.”

to record the incredible beauty and biodiversity of these regions. Don’t take our word for it: Says Barack Obama of Attenborough: “A great educator as well as a great naturalist.”

Immortalized by Shakespeare as a hunchbacked murderer, Richard III is one of English history’s best known and least understood monarchs. In 2012 his skeleton was uncovered in a UK parking lot, reigniting debate about this divisive historical figure and sparked numerous articles, television programs and movies about his true character. ![Richard III: England's Most Controversial King by [Skidmore, Chris]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51kkyj5fX6L.jpg) In Richard III: England’s Most Controversial King (St. Martin’s Press, $29.99) acclaimed historian Chris Skidmore has written the authoritative biography of a man alternately praised as a saint and cursed as a villain. Was he really a power-crazed monster who killed his nephews, or the victim of the first political smear campaign conducted by the Tudors?

In Richard III: England’s Most Controversial King (St. Martin’s Press, $29.99) acclaimed historian Chris Skidmore has written the authoritative biography of a man alternately praised as a saint and cursed as a villain. Was he really a power-crazed monster who killed his nephews, or the victim of the first political smear campaign conducted by the Tudors?

In Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and Their Rendezvous with American History (Liveright, $28.95) Yunte Huang recounts the peculiar, and often ironic, rise of Chang and Eng from sideshow curiosity to Southern gentry—an unlikely story that exposes the foibles of a young republic eager to tyrannize and delight in the abnormal. Famous for their quick wit (they once refunded a one-eyed man half his ticket because he “couldn’t see as much as the others”), Chang and Eng became a nationwide sensation, heralded as living symbols of the humbugged freak. Their unrivaled success quickened the birth of mass entertainment in America, leading to the minstrel show and the rise of showmen like P.T. Barnum.

And it is here that we encounter a twist. Miraculously, despite the 1790 Naturalization Act which limited citizenship to “free white persons” (until 1952), Chang and Eng became American citizens under the Superior Court of North Carolina. They then went on to marry two white sisters—Sarah and Adelaide Yates—and father 23 children despite the interracial marriage ban (in place until 1967). They owned 18 slaves and became staunch advocates for the Confederacy, so much so that their sons fought for the South during the Civil War. Huang reveals that it was perhaps their very “otherness” that worked for them: they were neither one individual, or quite two.

And it is here that we encounter a twist. Miraculously, despite the 1790 Naturalization Act which limited citizenship to “free white persons” (until 1952), Chang and Eng became American citizens under the Superior Court of North Carolina. They then went on to marry two white sisters—Sarah and Adelaide Yates—and father 23 children despite the interracial marriage ban (in place until 1967). They owned 18 slaves and became staunch advocates for the Confederacy, so much so that their sons fought for the South during the Civil War. Huang reveals that it was perhaps their very “otherness” that worked for them: they were neither one individual, or quite two.

Forty-five years after Bruce Lee’s sudden death at 32, Matthew Polly has written the definitive account of Lee’s life. Following a decade of research, dozens of rarely seen photographs, and more than one hundred interviews with Lee’s family and friends, Bruce Lee: A Life (Simon & Schuster, $35) breaks down the myths surrounding Bruce Lee and delivers a complex, humane portrait of the icon.

The book explores Lee’s early years: his career as a child star in Hong Kong cinema; his actor father’s struggles with opium addiction; his troublemaking teen years; and his beginnings as a martial arts instructor. Polly chronicles the trajectory of Lee’s acting career in Hollywood, from his frustration seeing role after role he auditioned for go to a white actors in eye makeup, to his eventual triumph as a leading man, to his challenges juggling a sky-rocketing career with his duties as a father and husband. Polly also sheds light on Bruce Lee’s shocking end—which is to this day is still shrouded in mystery—by offering an alternative theory behind his tragic demise.

The book explores Lee’s early years: his career as a child star in Hong Kong cinema; his actor father’s struggles with opium addiction; his troublemaking teen years; and his beginnings as a martial arts instructor. Polly chronicles the trajectory of Lee’s acting career in Hollywood, from his frustration seeing role after role he auditioned for go to a white actors in eye makeup, to his eventual triumph as a leading man, to his challenges juggling a sky-rocketing career with his duties as a father and husband. Polly also sheds light on Bruce Lee’s shocking end—which is to this day is still shrouded in mystery—by offering an alternative theory behind his tragic demise.

Marion Ross’ warm and candid memoir, My Days: Happy and Otherwise (Kensington, $26), brims with loving recollections from the award-winning Happy Days team—from break-out star Henry Winkler to Cunningham “wild child” Erin Moran. The actress shares what it was like to be a starry-eyed young girl with dreams in poor, rural Minnesota, and the resilience, sacrifices, and determination it took to make them come true.  She recalls her early years in the business, being in the company of such luminaries as Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall and Noel Coward, yet always feeling the Hollywood outsider—a painful invisibility that mirrored her own childhood. She reveals the absolute joys of playing a wife and mother on TV, and the struggles of maintaining those roles in real life. But among Ross’s most heart-rending recollections are those of finally finding a soulmate—another secret hope of hers made true well beyond her expectations.

She recalls her early years in the business, being in the company of such luminaries as Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall and Noel Coward, yet always feeling the Hollywood outsider—a painful invisibility that mirrored her own childhood. She reveals the absolute joys of playing a wife and mother on TV, and the struggles of maintaining those roles in real life. But among Ross’s most heart-rending recollections are those of finally finding a soulmate—another secret hope of hers made true well beyond her expectations.

Writing The Restless Wave: Good Times, Just Causes, Great Fights, and Other Appreciations (Simon & Schuster, $30) while confronting a mortal illness, John McCain looks back with appreciation on his years in the Senate, his historic 2008 campaign for the presidency against Barack Obama, and his crusades on behalf of democracy and human rights in Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

Always the fighter, McCain attacks the “spurious nationalism” and political polarization afflicting American policy. He makes an impassioned case for democratic internationalism and bi-partisanship. He tells stories of his most satisfying moments of public service, including his work with another giant of the Senate, Edward M. Kennedy. McCain recalls his disagreements with several presidents, and minces no words in his objections to some of Frump’s statements and policies. At the same time, he offers a positive vision of America that looks beyond the evil Frump.

Remembered primarily as America’s leading, most influential physician, Benjamin Rush led the Founding Fathers in calling for abolition of slavery, equal rights for women, improved medical care for injured troops, free health care for the poor, slum clearance, citywide sanitation, an end to child labor, free universal public education, humane treatment and therapy for the mentally ill, prison reform and an end to capital punishment.

Using archival material from Edinburgh, London, Paris, and Philadelphia, as well as significant new materials from Rush’s descendants and historical societies, Harlow Giles Unger’s Dr. Benjamin Rush: The Founding Father Who Healed a Wounded Nation (Da Capo Press, $28) restores Benjamin Rush to his rightful place in American history as the Founding Father of modern American medical care and psychiatry.

In 1929, 30-year-old gangster Al Capone ruled both Chicago’s underworld and its corrupt government. To a public who scorned Prohibition, “Scarface” became a local hero and national celebrity. But after the brutal St. Valentine’s Day Massacre transformed Capone into Public Enemy Number One, the federal government found an unlikely new hero in a 27-year-old Prohibition agent named Eliot Ness. Chosen to head the legendary law enforcement team known as “The Untouchables,” Ness set his sights on crippling Capone’s criminal empire.

Scarface and the Untouchable: Al Capone, Eliot Ness, and the Battle for Chicago (William Morrow, $29.99) draws upon decades of primary source research—including the personal papers of Ness and his associates, newly released federal files, and long-forgotten crime magazines containing interviews with the gangsters and G-men themselves. Authors Max Allan Collins and A. Brad Schwartz have recaptured a bygone bullet-ridden era while uncovering the previously unrevealed truth behind Scarface’s downfall. Together they have crafted the definitive work on Capone, Ness, and the battle for Chicago.

Arthur Fellig’s ability to arrive at a crime scene just as the cops did was so uncanny that he renamed himself “Weegee,” claiming that he functioned as a human Ouija board. Weegee documented better than any other photographer the crime, grit, and complex humanity of mid-century New York City. In Flash, we get a portrait not only of the man (both flawed and deeply talented, with generous appetites for publicity, women, and hot pastrami) but also of the fascinating time and place that he occupied.

So we finally have the first biography of the man with the camera in Christopher Bonanos’Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous (Henry Holt, $32). Weegee lived a life just as worthy of documentation as the scenes he captured. With Flash, we have an unprecedented and ultimately moving view of the man now regarded as an innovator and a pioneer, an artist as well as a newsman, whose photographs are among most powerful images of urban existence ever made.

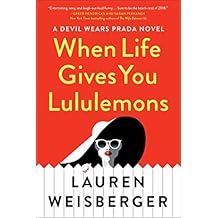

Karolina Hartwell is as A-list as they come. She’s the former face of L’Oreal. A mega-supermodel recognized the world over. And now, the gorgeous wife of the newly elected senator from New York, Graham, who also has his eye on the presidency. It’s all very Kennedy-esque, right down to the public philandering and Karolina’s arrest for a DUI—with a Suburban full of other people’s children. We can’t reveal more because we just pissed in pour pants. It’s that funny!

Karolina Hartwell is as A-list as they come. She’s the former face of L’Oreal. A mega-supermodel recognized the world over. And now, the gorgeous wife of the newly elected senator from New York, Graham, who also has his eye on the presidency. It’s all very Kennedy-esque, right down to the public philandering and Karolina’s arrest for a DUI—with a Suburban full of other people’s children. We can’t reveal more because we just pissed in pour pants. It’s that funny! He provides readers with a page-turning, character-driven narrative, using the personal stories of

He provides readers with a page-turning, character-driven narrative, using the personal stories of Taking a wide-angle view of America—and Texas—in the Eisenhower era, Graham reveals how the film and its production mark the rise of America as a superpower, the ascent of Hollywood celebrity, and the flowering of Texas culture as mythology. Featuring James Dean, Rock Hudson, and Elizabeth Taylor, Giant dramatizes a family saga against the background of the oil industry and its impact upon ranching culture—think Spindletop Hill in Beaumont, Texas, and the fabled King Ranch in South Texas. Almost as good as the film.

Taking a wide-angle view of America—and Texas—in the Eisenhower era, Graham reveals how the film and its production mark the rise of America as a superpower, the ascent of Hollywood celebrity, and the flowering of Texas culture as mythology. Featuring James Dean, Rock Hudson, and Elizabeth Taylor, Giant dramatizes a family saga against the background of the oil industry and its impact upon ranching culture—think Spindletop Hill in Beaumont, Texas, and the fabled King Ranch in South Texas. Almost as good as the film. Tackling a wide range of forms with gusto (including ballet, hip-hop, jazz, ballroom, tap, contact improvisation, swing),

Tackling a wide range of forms with gusto (including ballet, hip-hop, jazz, ballroom, tap, contact improvisation, swing),